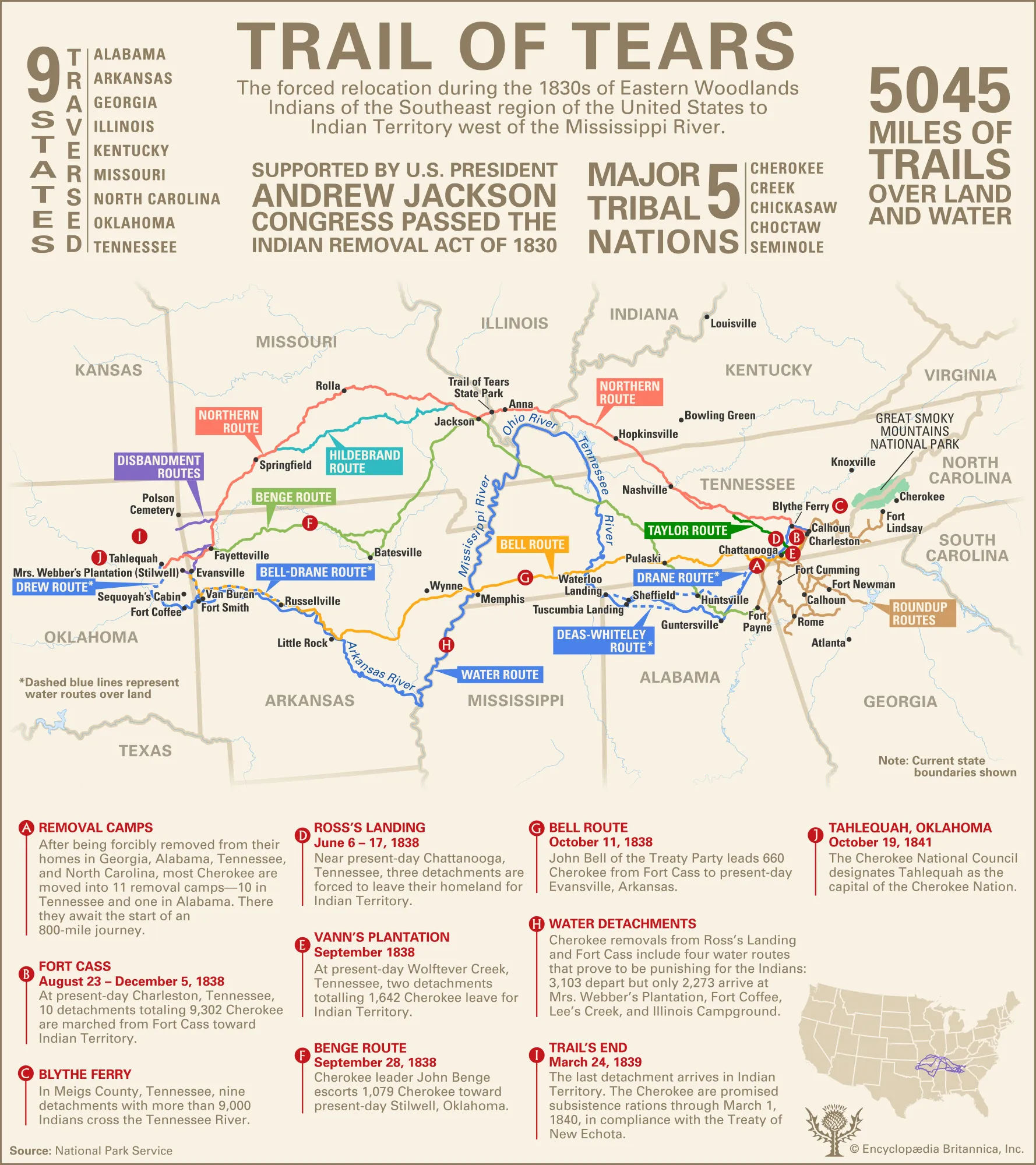

At the beginning of the 1830s, nearly 125,000 Native Americans lived on millions of acres of land in Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, North Carolina and Florida–land their ancestors had occupied and cultivated for generations. By the end of the decade, very few natives remained anywhere in the southeastern United States. Working on behalf of white settlers who wanted to grow cotton on the Indians’ land, the federal government forced them to leave their homelands and walk hundreds of miles to a specially designated “Indian territory” across the Mississippi River.

Taking the journey through an unusually cold winter, they suffered terribly from exposure, disease, and starvation, killing several thousand people while en route to their new designated reserve. They were also attacked by locals and economically exploited - starving Indians were charged a dollar a head (equal to $24.01 today) to cross the Ohio River, which typically charged twelve cents, equal to $2.88 today.

Indian Removal

Andrew Jackson had long been an advocate of what he called “Indian removal.” As an Army general, he had spent years leading brutal campaigns against the Creeks in Georgia and Alabama and the Seminoles in Florida–campaigns that resulted in the transfer of hundreds of thousands of acres of land from Indian nations to white farmers. As president, he continued this genocide. In 1830, he signed the Indian Removal Act, which gave the federal government the power to exchange Native-held land in the cotton kingdom east of the Mississippi for land to the west, in the “Indian colonization zone” that the United States had acquired as part of the Louisiana Purchase. (This “Indian territory” was located in present-day Oklahoma.)

The law required the government to negotiate removal treaties fairly, voluntarily and peacefully: It did not permit the president or anyone else to coerce Native nations into giving up their land. However, President Jackson and his government frequently ignored the letter of the law and forced Native Americans to vacate lands they had lived on for generations. In the winter of 1831, under threat of invasion by the U.S. Army, the Choctaw became the first nation to be expelled from its land altogether. They made the journey to Indian Territory on foot (some “bound in chains and marched double file,” one historian writes) and without any food, supplies or other help from the government. Thousands of people died along the way. It was, one Choctaw leader told an Alabama newspaper, a “trail of tears and death.”

The Trail of Tears

The Indian-removal process continued. In 1836, the federal government drove the Creeks from their land for the last time: 3,500 of the 15,000 Creeks who set out for Oklahoma did not survive the trip.

The Cherokee people were divided: What was the best way to handle the government’s determination to get its hands on their territory? Some wanted to stay and fight. Others thought it was more pragmatic to agree to leave in exchange for money and other concessions. In 1835, a few self-appointed representatives of the Cherokee nation negotiated the Treaty of New Echota, which traded all Cherokee land east of the Mississippi for $5 million, relocation assistance and compensation for lost property. To the federal government, the treaty was a done deal, but many of the Cherokee felt betrayed; after all, the negotiators did not represent the tribal government or anyone else. “The instrument in question is not the act of our nation,” wrote the nation’s principal chief, John Ross, in a letter to the U.S. Senate protesting the treaty. “We are not parties to its covenants; it has not received the sanction of our people.” Nearly 16,000 Cherokees signed Ross’s petition, but Congress approved the treaty anyway.

By 1838, only about 2,000 Cherokees had left their Georgia homeland for Indian Territory. President Martin Van Buren sent General Winfield Scott and 7,000 soldiers to expedite the removal process. Scott and his troops forced the Cherokee into stockades at bayonet point while his men looted their homes and belongings. Then, they marched the Indians more than 1,200 miles to Indian Territory. Whooping cough, typhus, dysentery, cholera and starvation were epidemic along the way, and historians estimate that more than 5,000 Cherokee died as a result of the journey.

By 1840, tens of thousands of Native Americans had been driven off of their land in the southeastern states and forced to move across the Mississippi to Indian Territory. The federal government promised that their new land would remain unmolested forever, but as the line of white settlement pushed westward, “Indian Country” shrank and shrank. In 1907, Oklahoma became a state and Indian Territory was gone for good.

Megathreads and spaces to hang out:

reminders:

- 💚 You nerds can join specific comms to see posts about all sorts of topics

- 💙 Hexbear’s algorithm prioritizes comments over upbears

- 💜 Sorting by new you nerd

- 🌈 If you ever want to make your own megathread, you can reserve a spot here nerd

- 🐶 Join the unofficial Hexbear-adjacent Mastodon instance toots.matapacos.dog

Links To Resources (Aid and Theory):

Aid:

Theory: