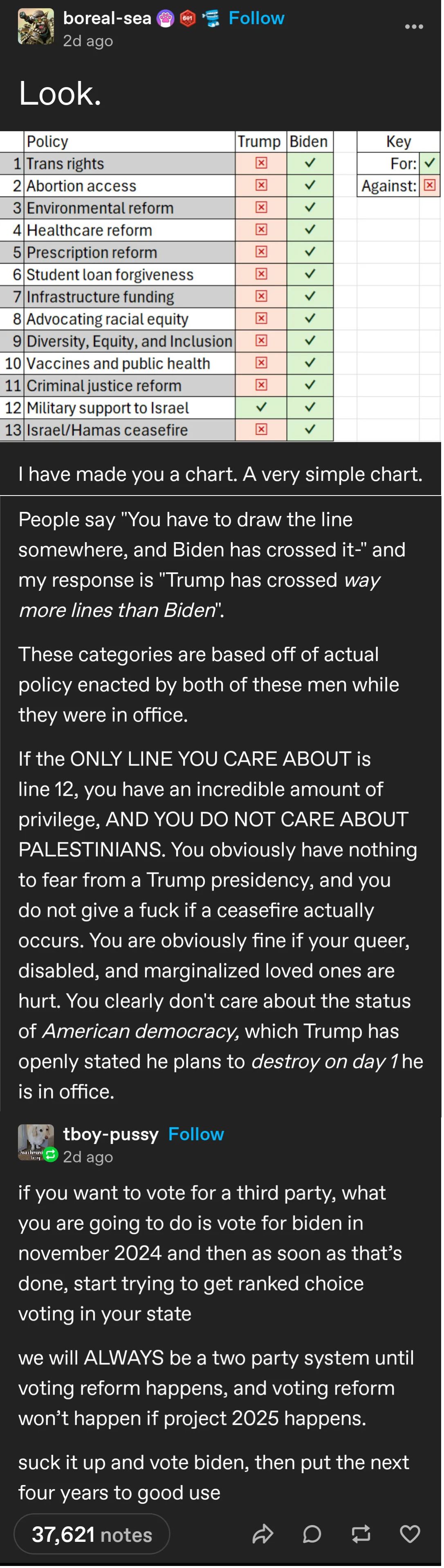

Image is of Bolivian President Luis Arce (center, with glasses) face-to-face with General Zuñiga (in camouflage) during the coup attempt.

On the 26th of June, while Hexbear was in an 8-hour hibernation, General Juan José Zuñiga marched 200 troops and some armored vehicles on the government palace in an attempt to overthrow the democratically elected government of Luis Arce. This is somewhat reminiscent of Jeanine Anez's coup in November 2019 where she overthrew the socialist president Evo Morales, but while that coup was due to a colour revolution likely orchestrated by the United States and had at least a tiny amount of political/public legitimacy and "followed the rules" in a certain sense (as Morales was trying to abolish presidential term limits, which is only evil if a socialist is doing it), this was a much more naked attempted seizure of power by a military general.

This coup was quickly terminated without even a momentary transfer of power. Democracy was saved.

Despite being in the same party, Morales and Arce have increasingly been in opposition. Morales champions anti-imperialism, rights for indigneous people, and poverty reduction. This last one especially has been threatened by Arce, though it's not entirely his fault, as the Bolivian economy is threatened by the same crisis affecting so many developing economies around the world right now - say it with me now - a lack of dollars and mounting debt. The US Federal Reserve is carrying out a bloody offensive against the world's poor, and this has combined nastily with a rather uninspiring "post"-coronavirus economic recovery in Bolivia, as well as diminishing natural gas production (and thus less exports with which to earn dollars).

While the coup was ongoing, Morales banded behind the government. Afterwards, however, Morales expressed his skepticism about whether the coup was, in fact, genuine, calling for an independent investigation into it, and saying that Arce “disrespected the truth, deceived us, lied, not only to the Bolivian people but to the whole world." This is because General Zuñiga made a series of very interesting statements to his family and colleagues, saying that Arce had "betrayed" him, and saying that Arce had told him “‘The situation is very screwed up, very critical. It is necessary to prepare something to raise my popularity.'" This does check out on the surface level, at least: Arce has suffered increasing unpopularity as the economy has suffered.

Interestingly, Morales' narrative has been supported by the anarchocapitalist leader of Argentina, Javier Milei, who is currently busy completely destroying his own country and stripping the copper out of the walls to give to American capitalists. Milei said that the coup attempt was "fraudulent". Meanwhile, those inside MAS opposed to Morales' accusations of a false coup have accused him of allying with the fascist right and becoming an instrument of imperialism.

The COTW (Country of the Week) label is designed to spur discussion and debate about a specific country every week in order to help the community gain greater understanding of the domestic situation of often-understudied nations. If you've wanted to talk about the country or share your experiences, but have never found a relevant place to do so, now is your chance! However, don't worry - this is still a general news megathread where you can post about ongoing events from any country.

The Country of the Week is Bolivia! Feel free to chime in with books, essays, longform articles, even stories and anecdotes or rants. More detail here.

Please check out the HexAtlas!

The bulletins site is here!

The RSS feed is here.

Last week's thread is here.

Israel-Palestine Conflict

Sources on the fighting in Palestine against Israel. In general, CW for footage of battles, explosions, dead people, and so on:

UNRWA daily-ish reports on Israel's destruction and siege of Gaza and the West Bank.

English-language Palestinian Marxist-Leninist twitter account. Alt here.

English-language twitter account that collates news (and has automated posting when the person running it goes to sleep).

Arab-language twitter account with videos and images of fighting.

English-language (with some Arab retweets) Twitter account based in Lebanon. - Telegram is @IbnRiad.

English-language Palestinian Twitter account which reports on news from the Resistance Axis. - Telegram is @EyesOnSouth.

English-language Twitter account in the same group as the previous two. - Telegram here.

English-language PalestineResist telegram channel.

More telegram channels here for those interested.

Various sources that are covering the Ukraine conflict are also covering the one in Palestine, like Rybar.

Russia-Ukraine Conflict

Examples of Ukrainian Nazis and fascists

Examples of racism/euro-centrism during the Russia-Ukraine conflict

Sources:

Defense Politics Asia's youtube channel and their map. Their youtube channel has substantially diminished in quality but the map is still useful.

Moon of Alabama, which tends to have interesting analysis. Avoid the comment section.

Understanding War and the Saker: reactionary sources that have occasional insights on the war.

Alexander Mercouris, who does daily videos on the conflict. While he is a reactionary and surrounds himself with likeminded people, his daily update videos are relatively brainworm-free and good if you don't want to follow Russian telegram channels to get news. He also co-hosts The Duran, which is more explicitly conservative, racist, sexist, transphobic, anti-communist, etc when guests are invited on, but is just about tolerable when it's just the two of them if you want a little more analysis.

On the ground: Patrick Lancaster, an independent and very good journalist reporting in the warzone on the separatists' side.

Unedited videos of Russian/Ukrainian press conferences and speeches.

Pro-Russian Telegram Channels:

Again, CW for anti-LGBT and racist, sexist, etc speech, as well as combat footage.

https://t.me/aleksandr_skif ~ DPR's former Defense Minister and Colonel in the DPR's forces. Russian language.

https://t.me/Slavyangrad ~ A few different pro-Russian people gather frequent content for this channel (~100 posts per day), some socialist, but all socially reactionary. If you can only tolerate using one Russian telegram channel, I would recommend this one.

https://t.me/s/levigodman ~ Does daily update posts.

https://t.me/patricklancasternewstoday ~ Patrick Lancaster's telegram channel.

https://t.me/gonzowarr ~ A big Russian commentator.

https://t.me/rybar ~ One of, if not the, biggest Russian telegram channels focussing on the war out there. Actually quite balanced, maybe even pessimistic about Russia. Produces interesting and useful maps.

https://t.me/epoddubny ~ Russian language.

https://t.me/boris_rozhin ~ Russian language.

https://t.me/mod_russia_en ~ Russian Ministry of Defense. Does daily, if rather bland updates on the number of Ukrainians killed, etc. The figures appear to be approximately accurate; if you want, reduce all numbers by 25% as a 'propaganda tax', if you don't believe them. Does not cover everything, for obvious reasons, and virtually never details Russian losses.

https://t.me/UkraineHumanRightsAbuses ~ Pro-Russian, documents abuses that Ukraine commits.

Pro-Ukraine Telegram Channels:

Almost every Western media outlet.

https://discord.gg/projectowl ~ Pro-Ukrainian OSINT Discord.

https://t.me/ice_inii ~ Alleged Ukrainian account with a rather cynical take on the entire thing.

what is it with Nazi states and announcing the approximate date of their counteroffensives in advance so that the other side can prepare